Non-Anticoagulant Rodent Poisons

NO Poison is a Good Poison

Dr. Laurel Serieys, world’s expert on rodent poisoning of bobcats tells us:

“Often people inquire, after learning the harmful impacts of anticoagulant poisons, what poisons may be used in substitution for anticoagulants.

The truth is that NO POISON IS A GOOD POISON – in other words, no poison available on the market in the United States poses no risk to wildlife.

Beyond considering the impacts of secondary exposure of wildlife to poisons, don’t forget that nontarget wildlife can too directly consume the poisons.

We know a lot more about some poisons than others.

Because anticoagulant rodenticides are the most commonly used method of rodent control used worldwide, more research concerning the negative impacts of this poison on wildlife have been conducted.

However, even for this poison, there are MANY unknowns!

The reality is that it is exceedingly difficult to know what happens to wildlife once they ingest poisons.

If there is an absence of data regarding how some compounds affect wildlife (i.e., vitamin D3 cholecalciferol, zinc phosphide, or bromethelin), it does not mean it poses no risk to wildlife.”

Cholecalciferol/Vitamin D3

Here are links to the facts about cholecalciferol.

1. www.petpoisonhelpline.com

Poisonous to: Cats, Dogs

Level of toxicity: Generally moderate to severe

“This is one of the most dangerous mouse and rat poisons on the market and unfortunately, seems to be gaining in popularity.”

“Cholecalciferol is one of the most potent mouse and rat poisons on the market. When ingested in toxic amounts, cholecalciferol, or activated vitamin D3, can cause life-threatening elevations in blood calcium and left untreated can result in kidney failure. Common signs of poisoning may not be evident for 1-3 days, when the poison has already resulted in significant and potentially permanent damage to the body. Increased thirst and urination, weakness, lethargy, decreased appetite, and vomiting may be seen. Acute kidney failure usually develops 2-3 days after ingestion of this type of mouse and rat poison.”

“Unfortunately, cholecalciferol mouse and rat poison does not have an antidote and is one of the most challenging poisoning cases to treat as hospitalization, frequent laboratory monitoring, and expensive therapy is often required for a positive outcome.”

“Cholecalciferol has a very narrow margin of safety, which means that even small ingestion of this poison can result in severe clinical signs or death. Toxic ingestions must be treated quickly and appropriately to prevent kidney failure.“

2. www.drugs.com

“However, in practice it has been found that use of cholecalciferol in rodenticides represents a significant hazard to other animals, such as dogs and cats.”

“Cholecalciferol produces hypercalcemia, which results in systemic calcification of soft tissue, leading to renal failure, cardiac abnormalities, hypertension, and Central nervous system depression.”

3. www.pethealthnetwork.com

Dr. Justine Lee, an expert on emergency care of pets, states –

“As an emergency critical care veterinary specialist, this is my most hated type of poisoning. Only a small amount can result in severe poisoning in both dogs and cats. This type of mouse and rat poison results in an increased amount of calcium in the body, leading to kidney failure. Unfortunately, this type has no antidote, and is very expensive to treat, as pets typically need to be hospitalized for 3-7 days on aggressive therapy.“

4. vet.purdue.edu

From the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory:

“RODENTICIDE REVOLUTION: D-CON SAYS, “GOOD-BYE ANTICOAGULANTS, HELLO VITAMIN D

In August of 2018, d-CON, one of the most common rodenticides in the United States, transitioned from anticoagulant active ingredients such as brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difethialone, and diphacinone to cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3).

Rodenticides are amongst the most common toxins ingested by cats and dogs, so it’s imperative that veterinary professionals be aware of this change and understand its medical implications.”

5. www.urban-wildlife.org/IUWC2017, page 118

From talk by Melissa Booker, Navy Wildlife Biologist.

Recent research shows that rodents can play a role in spreading cholecalciferol. This occurs not from secondary poisoning from eating the rodents, but from rats gathering cholecalciferol pellets away from bait stations and bringing it to their lairs. Foxes can then gain access to the pellets, eat them, and become fatalities.

Bromethalin

From an EPA document:

“Bromethalin is a neurotoxin. Clinically, this results in swelling of the brain (cerebral edema). In general, severe bromethalin poisonings are very concerning for clinicians because of less human experience with them and, unlike the anticoagulant rodenticides, there is no specific diagnostic test or antidote. Given that bromethalin targets the central nervous system, there is concern that the developing brain of young children may be particularly susceptible to the effects of bromethalin.“

From HealthyPets.mercola.com:

“Since 2011, the national Pet Poison Helpline has reported a 65 percent increase in bromethalin poisoning in pets.”

“Bromethalin is a fast-acting neurotoxin that affects the brain and liver. In pets, signs of brain swelling and central nervous system disturbance appear within 2 to 24 hours of ingestion.”

According to the National Park Service, bromethalin was detected in 10 out of 16 mountain lions tested in the Santa Monica Mountains between 7/2020 and 8/2022.

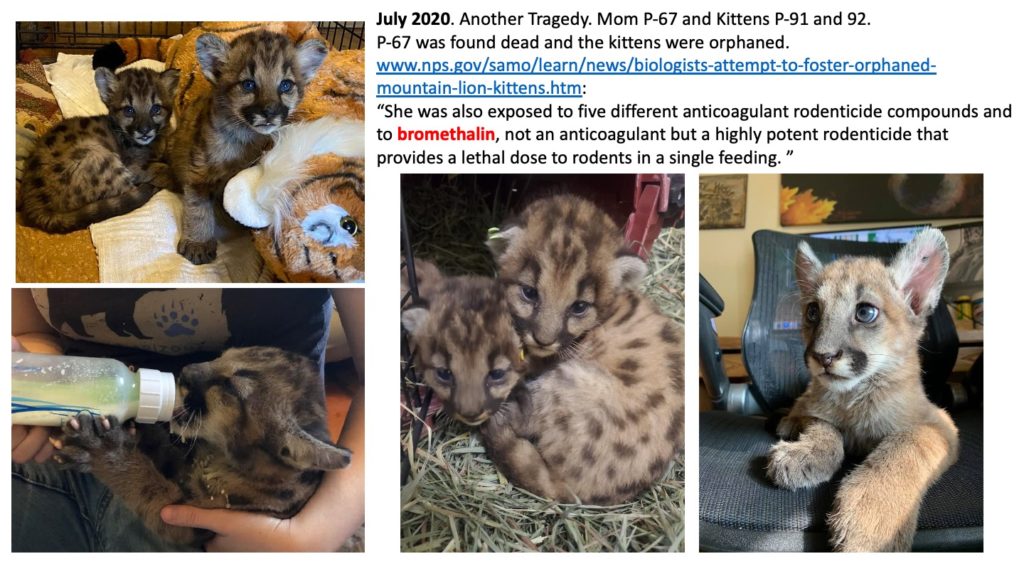

1) P-67. From National Park Service October 2020 press release – Mountain lion mom, P-67, found dead with anticoagulants AND non-anticoagulant bromethalin.

She was a mother taking care of two kittens, P-91 and P-92, who were rescued by the National Park Service.

Quote from the news bulletin –

“She was also exposed to five different anticoagulant rodenticide compounds and to bromethalin, not an anticoagulant but a highly potent rodenticide that provides a lethal dose to rodents in a single feeding.”

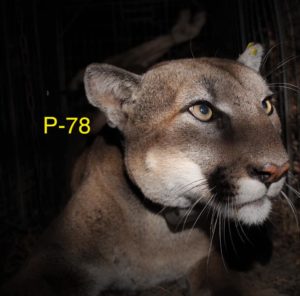

2) P-78. NPS March 2021 Instagram Post – “According to recent necropsy results, he also tested positive to exposure to five anticoagulant rodenticide compounds and bromethalin.”

The Los Angeles Times, a consistent supporter of our wildlife, noted about P-78 in “Editorial: When will mountain lions in Los Angeles County stop being killed by cars and rat poison?” – “Numerous studies on California wildlife show that that rodenticides have widely poisoned, and sometimes killed, mountain lions and other animals.”

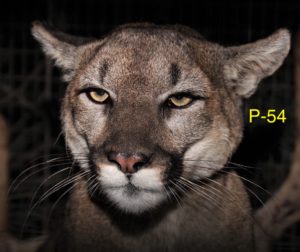

3) P-54. NPS September 7, 2022 Press Release – “Adult female mountain lion P-54 and her four full-term fetuses were exposed to multiple anticoagulant rodenticides.”

“She had been exposed to five compounds (brodifacoum, bromadiolone, chlorophacinone, difethialone, and diphacinone). The neurotoxic rodenticide bromethalin was also detected in her abdominal fat tissue.“

The notable point here is the presence of bromethalin.

It is NOT an anticoagulant rodent poison.

It is sometimes claimed that non-anticoagulants do not spread up the food chain to higher predators. This P-67 incident is a counter-example – mountain lions obviously do not eat rodent poisons of any kind directly.

The bromethalin must have come up the food chain from rodents, raccoons, or another intermediate species.

More is learned from a 2019 paper from the University of Georgia, Evidence of bromethalin toxicosis in feral San Francisco “Telegraph Hill” conures. It notes an increase in bromethalin usage, and recommends more research to determine the sources and pathways that it follows to the poisoned animals.

Quote:

“Reports of animal and human exposure to bromethalin increased following 2008 EPA mandates designed to decrease the use of SGARs like brodifacoum and bromadiolone, which are known to cause unintended secondary toxicosis in wildlife. The Pet Poison Helpline saw a 65% increase in bromethalin toxicosis cases reported between 2011 and 2014. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals said it received 2791 calls regarding exposure to bromethalin-based poisonings in 2015.”

4) P-65. NPS September 26, 2022 Press Release – “Adult female P-65 is the first mountain lion in study to die of complications from mange.”

Mountain lions killed by rat poison usually bleed to death due to the anticoagulant action of the poison. This was a case of a mountain lion dying from rodent poison induced mange, which is what usually kills bobcats.

“Toxicological tests revealed that she was exposed to five different anticoagulant rodenticides, also known as rat poisons, and to bromethalin, a neurotoxic rodenticide. The five anticoagulant rodenticide compounds detected in P-65’s liver, brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difethialone, chlorophacinone, and diphacinone, included both first-generation and longer-lasting and faster-acting second-generation compounds.”

5) Tufts University publication on bromethalin poisoning of raptors. “New Study is First to Find Exposure to Neurotoxic Rodenticide Bromethalin in Birds of Prey“

6) Famed Los Angeles Griffith Park Mountain Lion P-22 had bromethalin too.

From the California Department of Fish & Wildlife – “Additionally, desmethylbromethalin, the toxic metabolite of bromethalin, was detected in his body fat. Bromethalin is a widely available rodenticide that targets the brain and affects the central nervous system. Signs of bromethalin poisoning include muscle tremors, seizures, hind limb paralysis, respiratory paralysis and eventually death.” – Final necropsy results released for mountain lion P-22

Strychnine

Strychnine is an example of a very dangerous and previously unpopular poison making a comeback. Stella McMillin, California Department of Fish and Wildlife Environmental Scientist for Toxicology finds –

“One rodenticide I’m keeping my eye on is strychnine. In California, we went nearly a decade without any reported cases of wildlife poisoned by strychnine. Now, in the last couple of years, we’ve had several. So, what’s going on? Is it just coincidence or is it due to the increased regulation of anticoagulant rodenticides?” An article from their Wildlife Investigations Laboratory on this – “Some Perspectives on Rodenticides”

The California Department of Pesticide Regulation website on strychnine states “CDFW has also seen an increase in the number of strychnine-related wildlife losses in recent years.”

This poison has been historically almost abandoned due to its extreme danger. Strychnine has NO antidote and acts very quickly. Thus, it is especially dangerous. From a State of Michigan pesticide website, “Due to the rapid absorption and action of strychnine, treatment is impractical for wildlife, unless found immediately after ingestion.”

The Merck Veterinary Manual says – “Strychnine is highly toxic to most domestic animals. Malicious or accidental strychnine toxicosis occurs mainly in small animals, especially dogs and occasionally cats, and rarely in production animals. Most toxicosis occurs when nontarget species consume commercial baits. Young and large-breed sexually intact male dogs may be more likely to be affected.” Furthermore “There is no specific antidote for strychnine toxicosis.”

It has been banned in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the European Union.

Zinc Phosphide

The rodenticide zinc phosphide is commonly used for poisoning ground squirrels and gophers. Zinc phosphide is in the most dangerous category of poison in that it cannot be purchased at a store and requires a license for application. It is true that it is not as susceptible to secondary poisoning as the anticoagulants, however, it is perhaps the most dangerous in regard to primary poisoning!

One of the most comprehensive and authoritative documents on wildlife poisoning is from an Environmental Protection Agency report from 2004. See Potential Risks of Nine Rodenticides to Birds and Nontarget Mammals: A Comparative Approach.

Please see page 66 which states –

“Based on the comparative analysis model, zinc phosphide is ranked as the rodenticide posing the greatest potential primary risk to nontarget mammals, with brodifacoum ranked a distant second, and warfarin and bromadiolone an even more distant third and fourth.”

“These other three are the anticoagulants. Zinc phosphide is considered significantly more dangerous for direct poisoning of wildlife, pets, and children than the anticoagulant poisons.

This is especially startling considering the many users of parks and also wildlife. Here is a quote from the National Pesticide Information Center, co-sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency and Oregon State University, on their website.

“Young children and pets are most likely to be exposed to zinc phosphide by eating the bait pellets if they find them. Baits often have peanut butter, molasses, or other flavors that may attract dogs or children.”

It continues, stating – “Zinc phosphide is very toxic to birds, fish, and other wildlife if it is eaten. Pellets or grain containing zinc phosphide may attract birds in particular. All baits should be placed so they are out of reach of any pets, children, or non-target wildlife.”

Another EPA document states “The Agency has also determined that a single swallow of zinc phosphide bait may be fatal to a young child.”!!

Birds appear to be the most vulnerable animal to zinc phosphide. The US Dept. of Agriculture reports:

“Effects on birds: Zinc phosphide is highly toxic to wild birds. The most sensitive birds are geese. Pheasants, mourning doves, quail, mallard ducks, and the horned lark are also very susceptible to this compound. Blackbirds are less sensitive (U.S. National Library of Medicine. Hazardous Substances Databank. Bethesda, MD, 1995.10-9).”

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources website warns –

“All species of animals are subject to zinc phosphide poisoning, but avian species, specifically gallinaceous birds {pheasants, turkeys, grouse, chicken}, are the most seriously affected. In Michigan, wild turkeys, ring-necked pheasants, black and gray squirrels, Canada geese, and possibly white-tailed deer have died from zinc phosphide poisoning.”

Aluminum Phosphide/Fumitoxin

Parks and recreation areas are where people, especially children and pets, are in close contact with the earth, with picnicking and ball playing in grassy areas. It is imperative that we look to non-poisonous ways of controlling pests. We are in particular concerned with the inclusion of Fumitoxin as an option for rodent control.

The EPA has placed Fumitoxin in its highest toxicity category, “Category 1 Danger.” “Danger” means that the pesticide product is highly toxic if eaten, absorbed through the skin, or inhaled. If this is the case, the word “POISON” must also be included in red letters on the front panel of the pesticide product label.

The compound converts to a deadly phosphine gas when it comes in contact with moisture, eventually degrading into inorganic phosphate. This is a groundwater contaminant and contributes to ocean water quality degradation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported about Fumitoxin in 1997 that “burrowing fumigants will kill animals residing in treated burrows, so it is important to verify that burrows are occupied by target animals. Animals potentially affected by primary poisoning include nontarget rodents, burrowing owls, reptiles and amphibians, rabbits, raccoons, fox, weasel and skunk.”

Fumitoxin caused the death of a four-year-old girl and her 15-month-old sister in 2010 in Utah. It leaked into the basement of their home after being used to treat the family’s lawn for gophers. San Diego TV station CBS-8 reported on this story and implications locally. See below for more on this story.

More recently, January 2017, CNN reported it happened again in Amarillo, Texas. Four children died and five additional family members sent to the hospital from a product containing the same phosphine gas compound.

City of San Diego Incident

The City of San Diego, Parks and Recreation Department had been relying on Fumitoxin. but determined that it will control rodents with safer methods. San Diego TV station CBS-8 reported on this in a November 2012 story. Please watch the video and read the story.

Quoting:

“The City of San Diego, Parks and Recreation Department stopped using Fumitoxin in 2010. Maintenance manager David Long said he used to use it for gopher control in Balboa Park. Now he uses traps.

“(Traps) are safe. They’re underground. People aren’t going to get into them. You know when you’ve killed the gopher because you have a body,” said Long. Long said he changed to the non-toxic alternative out of concern for public safety. “We use traps now and it’s fairly effective,” said Long. “Even when we used Fumitoxin, we still had gophers. But I don’t believe our problem without Fumitoxin is any worse than it was with Fumitoxin.”

To learn more about San Diego’s practices, Citywide District Manager Dave Long can be contacted at 619-235-1165.